Use Range Maps to Simplify your ID Search

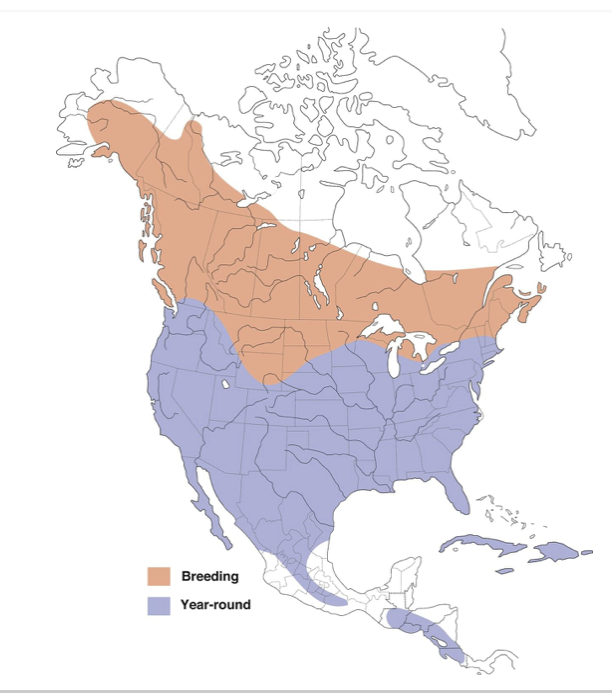

The map on the left shows us the range of the Red-Tailed Hawk, the most common hawk seen in the U.S., The map on the right is for the Hermit Warbler, a migrating species that is only found in a small area of the U.S., and only at certain times of the year.

What do these maps tell us?

For the hawk, it’s clear most of the United States has Red-Tailed hawks in it year-round. It’s generally not migratory, although it expands it’s territory during breeding season, so if it’s January in Winnipeg, seeing this species is quite unlikely, but in July? Much more likely. Here in the Bay Area, this is why it can seem like we have a Red-Tailed on every power pole in some parts of the region in winter — we do, because those northern Hawks move down here for the cold months and then shift back north again for breeding season. Red-tails are so common most places that I’ve generally told newer birders to assume a hawk-looking bird they see is one until they can prove it otherwise — and of course, Red-tails can vary a lot in size and coloration, just to make it more fun.

If you are birding in Michigan, and you’re trying to ID a warbler, a quick look at this range map will help you move on to other candidates, because the hermit warbler never visits that state (with a caveat: stay tuned). If you are on the west coast, the different colors give you a sense what time of year the bird might be in your area, whether it’s spring or fall migration, summer breeding season, or winter down in the tropics. Here in the Bay Area, for instance, we get some birds migrating through, but it should be noted a bird in migration doesn’t stay long, so if one is seen by another birder and reported, you may only have a day or so — or hours, or it’s already too late and it’s gone — to chase the bird. Years ago I was having lunch outside my office during spring migration when I had what I was convinced was a Baltimore Oriole land in a tree near me and start foraging. I passed the word on. By the time some other birders arrived within about 30 minutes, it had already moved on, and we never found it again, and so my sighting was never confirmed by someone actually qualified to make that ID. That’s how short our windows can be in migration some times.

This is the magical power of the Range Map: it can show you, at a glance, whether the species you are looking at is likely to be seen where you at at a given time of year. So if you can’t decide if that bird you saw is one of five candidates in your searching, the range maps may well help you eliminate a few of those from contention.

There’s always an exception

There is, of course, always exceptions to these range maps. I chose Hermit Warbler for my second example because one winter we had a Hermit Warbler take up residence in a tree in a local park, and stick around for a number of months. The range maps say this bird shouldn’t be there; the bird decided differently, and so many birders happily went and saw it as it hung out there for the winter.

Range maps aren’t perfect — but new birders have a tendency to jump on “REALLY SPECIAL BIRD” quickly and you should try to minimize that as much as possible (remember my tale of the not-really-a-black-vulture in the previous chapters?). Always assume it’s a common bird until you can prove it’s not; and the rarely the ID you think you’re making, the better the evidence you’ll want to show to convince people you’re correct. These strange, wonderful, unique birds do happen, but when that “REALLY SPECIAL BIRD” feeling hits you, you need to slow down, think it through and eliminate all other possibilities first.

Real life is fuzzy and complicated. Use range maps to eliminate the unlikely candidate species — until those are the only ones left. Then circle back and reconsider these crazy birds. New birders love to chase rarities and we all have a tendency to see rare birds everywhere when we’re new at this, because we don’t know any better. It’s important to remember, of course, that these rare birds are, well, rare. This wintering hermit warbler is a 1 in a decade bird, at least. So I always remind birders I work with to avoid jumping to the rare bird ID until you’ve made sure it’s not a common bird instead.

Bird ID of a bird you don’t know can be difficult, complicated and frustrating. Learning to use range maps can help you limit the number of possibilities quickly, and make the ID process a little faster and a little easier.

Here’s a simple tip that took me a few years to figure out, and I hope mentioning it will shorten your learning curve. When I’m out birding and I run into a bird I don’t know, I find myself searching through the field guide to try to come up with the right ID for it. The challenge is that there are often dozens of possibilities. Here in California, the field guides show about 700 possible species, but we can usually thin that out with a few basic decisions — for instance, is it duck-sized or robin-sized?

Still, you often end up with many options and it can be hard to narrow the field of possible candidates further. Here is where Range Maps can come into play.

Every field guide will show a range map for a specific species as part of it’s information. This will be generally a map of the part of the world where the bird can be found. This map is marked with different areas shown in various colors. For instance, here’s a range map for Red-Tailed Hawk (range maps courtesy of All About Birds, a wonderful resource when you’re trying to ID something)